What Happens When You Stop Running From Yourself

It was an eerie atmosphere that very first morning of my Vipassana meditation course; to hear the gong at 4am, step out into the icy cold darkness outside of the dorm, the moon lighting up the snow on the ground in silver, and the footsteps of the other participants crunching behind me on the walk to the meditation hall. I remembered I could neither talk to nor look at them, and that I was in for 10 days of sitting with my mind, for 10 hours a day. I also remembered the concerned expression on my parents’ faces the day before, when they had asked me, trying to be interested, but not able to hide their confusion: “and.. why? Do you do this?”

I had struggled to explain. Sure, I could have quoted the studies, the many examples of scientists proving reduced anxiety, improved sleep, or increased empathy from meditation. But the real reason was this: I had tapped into this new quality to life recently – and I wanted more of it. Well into my mid-20s, I had bought into the cultural myth that fulfillment is to be found in certain external circumstances. I had rushed through life’s activities on autopilot, trying to bring about certain experiences or seek out certain places to imbue life with meaning. Peace seemed always just around the corner, always just one thought away. Unexpectedly, meditation, as well as a number of psychedelic experiences, revealed to me that I’d been had: that that the constant undercurrent of mild anxiety was not normal life, and that my mind was not me. There appeared this other, totally new dimension to life, that no one had told me about: Being. It’s impossible to unsee.

So here I was, a declared “atheist”, following a path laid out by the Bhudda. Vipassana means “to see things as they really are.” This ancient technique, discovered by Siddhartha Gautama (aka “the Buddha”), aims to liberate us from suffering by uprooting its causes at the deepest level of the mind—our clinging to pleasant experiences and aversion to unpleasant ones. The idea: it is not what life presents to us that makes us happy or unhappy, it is our reactions to it. The method has been preserved over 2,500 years in the far Wast, and finally popularized globally by S.N. Goenka since the 60s. The courses are rigorous: 10 days of voluntary confinement, and intense meditation totaling 10 hours daily. The strict schedule includes simple vegetarian meals and enforced “noble silence”—no speech, gestures, or eye contact—except for questions to teachers.

Despite the harshness, Vipassana is not a religion or cult; The Bhudda was never interested in establishing “Bhuddism”. There is no leader, and no one profiting from the courses financially in any way. They are offered for free, based solely on donations from people that have previously completed the course and want to offer a chance for mental freedom to someone else. The method was given to other people by the Bhudda out of compassion, and it still retains this quality of being a ‘gift’ – up to you to take or leave. All teachers and staff on site are volunteers. Most importantly, we were repeatedly encouraged to keep only the aspects of the teaching that speak to us, and commit ourselves to the method only if we see real improvements in our own lives. Vipassana is not a teaching to be believed, it is a method to be practiced. I decided to give it a shot.

As I settled into my meditation cushion amongst the one hundred or so other participants, I felt a strange relief at what lay ahead of me, a kind of joyful apprehension of 10 days of doing nothing – truly nothing. Ten days of having nothing to say, and nothing to respond to, no one to be.

It is fascinating how long it takes for the mind to settle into this reality. Before moving into the actual Vipassana method, the entire first three days of the course are dedicated to quieting down the ‘monkey mind’– which has the habit of jumping from one thought to the other, often completely unrelated, as if hurrying from one branch to the next. Quieting the ‘monkey mind’ is like taming an animal – you can try to beat it into stillness with angry self-constraint, but then it will never be your friend. Its better to sit with it, quietly and calmly, until it slowly, gradually, begins to settle. Its like an agitated body of water – trying to control which way the waves go will only stir them up anew. The only way to calm water is to hold still.

I never before had the chance to observe what happens over the course of thirty hours of almost uninterrupted observation of my internal world: I experienced my own mind as a vast space, like a round sphere with permeable boundaries. In the middle of that sphere: I. Around me, my experiences – and those include my thoughts. They appeared and disappeared into and out of the sphere, some lingering and tugging at me for a while, others just there an instant. Some reached very near the center – loud, powerful, seductive. Those thoughts felt like they had a pull, and those were the ones that, over and over, would just grab me and take me with them.

I noticed my thoughts pass through different subject matters – the ones with the highest emotional charge came first. Relational matters, followed by organizational ones. By day three, my mind was hijacked by the meditation itself – ruminating about the increasing physical pain that was building up in my back, running through all possible seating positions, and wondering with increasing frequency and panic how on earth I was going to survive this.

Thankfully, I had some experience in meditation, and understood that all these thoughts didn’t make it any less successful – in fact, there is no such thing as being good or bad at meditation. It is a common misunderstanding that meditation is all about trying to empty our minds, that its about thinking as little as possible. Instead, it is about noticing when we got distracted, and returning to the object of concentration (in this case, the breath), over, and over, and over again, with gentle self-compassion. The moment we notice, we are present. We are conscious. And we begin again. This way, we slowly de-identify from our thoughts – which are nothing but conditioned behavior patterns – and instead identify with the calm presence behind them, regaining a sense of agency and peace over own lives.

In a Vipassana course, however, there is an additional challenge to simply exercising patience: the intense physical trial of sitting up for 10 hours straight for 10 days. I felt somewhat prepared: Yin Yoga had taught me to endure discomfort. But this pain pushed my limits. Chairs were permitted only for elderly people or those with special conditions, and once my left foot fell asleep in my cross-legged seat so completely I feared it was dead flesh. But a sharp pain below my left shoulder-blade soon muted out everything else. Shooting up into my neck and down into my back, it was difficult to stay in meditation and not abandon.

Peace, by day three, was nowhere to be found: my deep, unnoticed aversion towards the pain unfolded in an intense, internal struggle of anger. Every three seconds thoughts like ‘This is insane, they are crazy, this is too much, what is this good for!’ yelled through what felt like the big empty hall of my mind. But here begins the true practice of Vipassana: non-reactivity.

On day four, the course moves into the Vipassana method: the methodological scanning of body sensations. At the same time, a new rule is imposed: for at least one hour at a time, no movement. At all. Don’t shift your feet when they start falling asleep, don’t roll or pull down your shoulders when they ache, don’t scratch your nose when it tickles. I gave it a shot – and it changed everything. It had been my constant internal rejection of the sensations and my unconsious movements against them that had kept the suffering alive, and even the sensations themselves. Once something in me decided to just let it happen, to just let myself sink into pure observant awareness, it didn’t bother me anymore. It just was. Until it wasn’t. By the end of day four, the intense pain between my shoulder blades had disappeared. I could sit more or less comfortably and without any fear for the remaining 60 hours of meditation in this course. This gave me motivation and a deepening trust to give the other aspects of the teaching their fair chance as well.

Working with physical pain is a key component of a Vipassana course. It isn’t there to torture us or train our willpower, it is there to help us discover a hidden door at the depth of our psyche: if we step though, we find the mechanisms by which a neutral experience of the senses is transformed into a mental one laden with judgment. One that we reject or want more of. And we find also that, at this level of awareness, we are free to intervene.

By day five, I felt like I was in something like “present-bootcamp” – at times, my impatience grew almost overwhelming. Every little stimulus that my sharpened perception was picking up on – my stomach growling with hunger, someone sneezing on the other side of the room – sent me down an inner tantrum. But then again, I still had 7 ½ hours ahead of me that day, or 6 ½, or 5 ½… and eventually, it began to sink in: it is not by counting down that I was going to get through these. It was only by returning to the here and now. Only by observing my impatience like I had observed anything else so far. Only by surrendering to what was, over and over and over again. And critically, what I learned in Vipassana is how to do this: by pouring myself into my physical sensations.

It is impossible to feel something, and judge it at the same time. This is true for an aching knee as much as a pleasant vibration: the moment you think about it, you’ve left it; the moment you’re fully with it, you accept it. And in those moments, all agitation dissipates. At first, it is a constant back and forth – but each moment in presence is timeless. Each moment in presence is eternal. A Vipassana course leaves enough time to truly familiarize ourselves with this unusual state: equanimity. And what a liberation it is.

Halfway through the course, after a good 50 hours of meditation, it became clear that a true transformation had started taking place in me. In the vast sphere of my mind, I could now hear beyond the loud, seemingly important thoughts that had cluttered the center at first: there were unfinished phrases, moments and faces, floating melodies. Even further beyond, in the very distance, an even more subtle but constant activity: sparks of ideas, unfinished concepts, vague emotions. My mental pond had settled enough for me to see the ground. Creative ideas emerged from the depths—paintings, book plots, business models—so original I couldn’t understand their source. Perhaps it’s true that true creativity springs from a deep calm?

My senses, too, had sharpened. A cough from across the room would shake my body like an earthquake, and the intense smell of pealing clementines in during lunch breaks became my greatest delight. But the transformation was most evident when I was going to bed: laying in the dark, no music, no book, no phone anywhere near, I found my mind clear. Tranquil like a frozen lake. This was a completely new experience to me. At times, I had even used sleeping aids in the past, to finally force an unrestful sleep behind over my anxious rumination.

Now I went to bed, whether already sleepy or not, and felt no anxiety about whether or not I would sleep – after 10 hours of it that day, what would be so bad about just being with my mind a little while longer? I was entirely content with just laying there in the dark, enjoying feeling connected to the sensations in my body until sleep would eventually come.

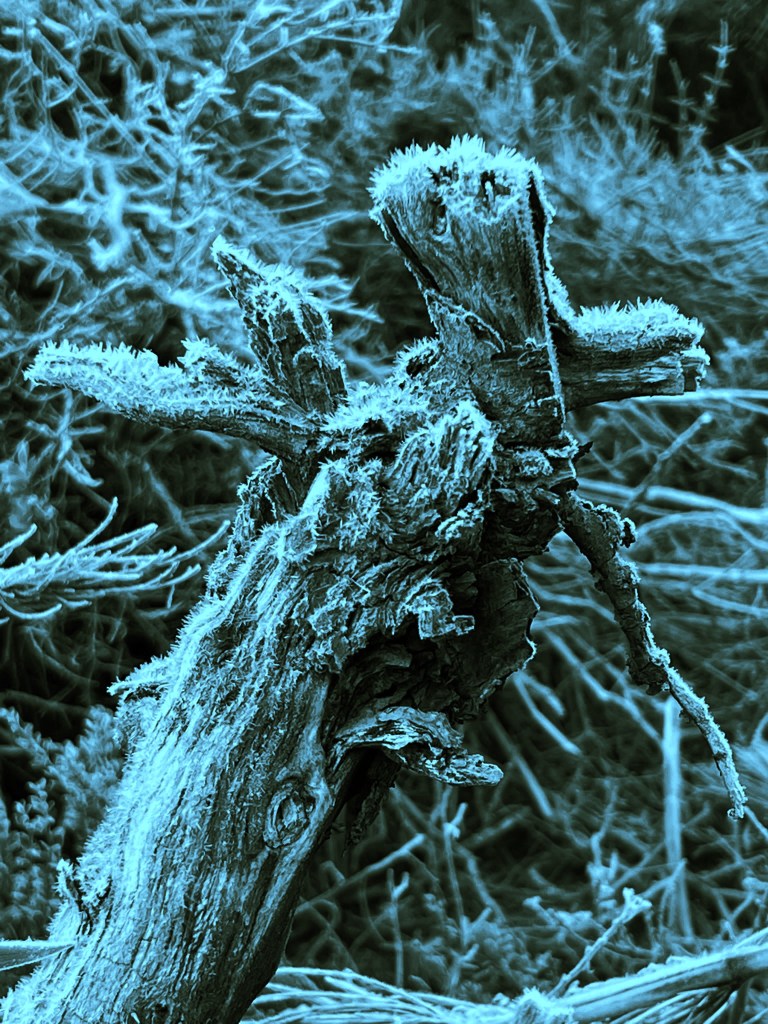

At daytime, in between meditations, I walked the snow and the icy forest trails in quietude, feeling an immense charge of appreciation at such simple things as a frozen leave, or the crisp air on my skin. One day, I noticed a frozen flower, an incredibly delicate sculpture of ice. I placed it on a snowed-in bench. I hoped it would lift the others’ spirits, like it had lifted mine. When I returned, other women had added frozen pine-cones, colorful barks, and other works of art that nature had come up with. Little by little, we created a small museum for each other, the museum of “natural beauty”.

Gestures like this moved me to tears. There was no direct interaction with the other women, we didn’t know each others’ names or stories. But the genuine well-wishing for each other was laden in the air. Why did this do so much to me? In ordinary life, could there be just as much kindness around me and more, and I just hadn’t noticed it?

However, it’s day seven and eight, the say, when things get really tough. And this seemed to be true. On a regular basis now, I heard someone shift and leave the meditation hall in tears. People were going through it, and I was too. I had left random distractions and my struggles with physical pain far behind, but the technique now took me working with much subtler cravings and aversions: my emotions. I suddenly became hyper-aware of that faint, but constant tension somewhere around my diaphragm: anxiety. We had been warned: it takes for the water to settle for the monsters to emerge; and mine was this constant companion.

It was a pattern I knew all too well: I was in it for the good times. Wanting certain feelings but not others had imbued my life with a constant quest for pleasure, and the pleasant moments with an ever-present fear – because nothing lasts forever. And wasn’t I supposed to feel peaceful here? These guys on Youtube had spoken about states of ecstasy and explosive bliss. Their spiritual materialism had made its way into my ambitious mind, and I thought “I’ll never be free”. In a growing spiral of disappointment and self-victimization, all I could feel was “anxiety”, and I hated it.

This evening, for the first time, I sought out the teacher, and asked her for help. “This anxious feeling in my chest” I said. “ I want to accept it, but I can’t. How can I accept something I can’t accept?”. “Just accept it”, she answered, and I was pissed. Thanks for nothing. Other people too had felt that psychological support in a Vipassana course is, at best, minimal. The code to real peace is cracked inside oneself, and oneself only, seems to be the idea. I heard of some breaking rules in order to support others, and its true that compassion has its place on this path. The one time I overslept, and one of my roommates decided to break her vow to shake me awake for meditation, I was filled with warmth and gratitude all day. And it was conducive. However, for me, the complete self-reliance ended up paying off.

I truly can’t explain how it happened – in just the same way our mind cannot understand what presence really is – only we can. But after 20 hours straight of trying to bring about “acceptance”, I suddenly let go. I surrendered. I was done rejecting the only life available to me – the one I lived right now. I was done trying to control. It happened the moment that “anxiety” became just a pressure, that labels became sensations. I felt like a body full of water in which a drop of ink falls – spreading peace and contentment throughout every part of me. It was still there, that sensation, but now it was simply experience. It was a shift in identification. “I” was no longer anxious, and annoyed by that – “I” was simply conscious. And “I” was spacious and still.

And here, I started to understand: it is not the experiences themselves we are afraid of, it is our own emotions, our reactions, to them. We aren’t scared of an exam, we are scared of discomfort. We aren’t scared of rejection, we are scared of feeling embarrassed. We aren’t just scared of losing someone we love, we are also scared of the crushing sadness. And for much of my life, I was anxious about anxiety. I understood the vicious cycle – intellectually; and tried to “accept” my way out. But acceptance is not found in the mind. It is found in the body. It is found by returning our awareness home.

“With this dimension comes a different kind of ‘knowing’. A knowing that that does not destroy the mystery of life but contains a deep love and reverence for all that is. A knowing of which the mind knows nothing.” – Eckart Tolle

And this, it dawned on me, is what “presence” really means. The present, so teachers and prophets since ancient times have been telling us, is where our entire life unfolds; where all its mystical depth is to be found. Yet my mind had turned even presence itself into a concept to think about. Before Vipassana, I tried to cultivate presence constantly thinking about what I was currently doing – and wondering why that didn’t bring peace. Despite my efforts, a feeling of detachment from my own self remained, and I had started to grow defeated about not ‘understanding’ what life was all about. Now I felt, with a clarity that blew all thoughts to pieces, that my mind never will. We cannot understand the truth. We can only be it. Life is about living it, and living happens in our bodies.

This type of equanimity doesn’t mean that we experience less happiness, or that we remove intensity from our joy or love. Not being attached doesn’t mean we no longer care. What revealed itself to me is that peace, joy and love are our natural states of being, and what we remove through meditation is the negativity that obscures it. When previously, joyful moments always had this tint of fear in them, that faintly ticking clock, I finally learned how to be with them fully. “Anica” – everything in the universe arises and passes, and we can learn to be in flow with that.

On day ten, the final day of the course, an excited, jubilating buzz seemed to fill the meditation hall. In order to help us transition back into the more (inter-)active parts of our lives, the silence was broken between meditations. It was funny how, at first, no one said a word – or maybe no one wanted do. For a few hours into the day, me and the other participants remained in silence voluntarily – now sometimes passing each other with a timid smile. I wasn’t willing to give up my inner sanctuaries just yet. But once the dam was broken, there was no stopping the floods. The evening breaks were filled with excited conversations. “From noble silence to noble chatter” S.N. Goenka called this day.

But more importantly, on day ten, we learned what all meditating was really about: love. Rather than sitting in the Vipassana-technique, we now learned the final essential from the Bhuddist tradition: “Metta-meditation”. Metta means “loving kindness”, and is intended to grow our capacity for love and compassion, to incline the mind towards kindness. It means wishing well without expecting anything in return – and isn’t that what true love really is?

From now on, every meditation sitting was to end with a few minutes of wishing well on ourselves and other beings – on all other beings. And here, the true purpose of Bhuddist meditation was revealed: it is not to relax ourselves, neither to make us happy – these are welcome side-effects. It is to become kind.

Concentration and equanimity serve a goal: to awaken the compassion rooted in recognizing our shared wish for happiness and for freedom from suffering. Sitting in introspection is not a selfish act of isolation – it is the access to true connection. With kindness as our goal, rather than turning away from the world, meditation is an act of turning towards it. To me, it felt like all the meditating before these final minutes of Metta were nothing but preparations for this ultimate aim. Feeling more connected to others, making life less about myself and myself less the center of the universe, making instead both others’ grievances as well as others’ joy my own – that is ultimately what has started to really “free” me.

Leaving the course, I didn’t feel like I had reached an endpoint. Rather, I had planted a fragile seed that would require daily nurturing. In times of enormous change and uncertainty on our planet, Vipassana has gifted me tools to surf life’s ups and downs rather than trying to force only the good times. It is becoming easier to greet each moment with curiosity rather than being captive to future fears. My progress unfolds in small steps – when anger that once burned for hours now dissipates sooner; when presence returns more quickly after distraction; when kindness becomes default rather than effortful practice. It’s an ongoing journey.

The path leads beyond concepts into direct experience— living presence embodied in breath, body sensations, acceptance, and love. For those willing to embrace its rigor with a leap of faith, Vipassana offers timeless wisdom for healing our minds and connecting our hearts, on this shared journey toward freedom.

Leave a comment